I met with José Oubrerie in February at the Standard Hotel in downtown Los Angeles, and later we drove to the Schindler House on Kings Road. He was in town for the book launch of Et in Suburbia Ego: José Oubrerie’s Miller House edited by Todd Gannon. The following is our conversation.

Orhan Ayyüce: What do you think about recent state of architecture education?

José Oubrerie: I think SCI-Arc is a great school. You have SCI-Arc, UIC, you have UCLA. We have a different way of where you stand and also what we try to do at Ohio State University. We show students a different way of working. For example in the past, Columbia University was fantastic, but it's been declining in the last years. The school was very active and also after that...

OA: Mark Wigley is very good.

JO: He doesn't like architecture.

OA: I saw him a few weeks ago in Shenzhen Biennale. He said something interesting. He said the architecture schools are mainly in crisis, which is good, and he said something that I liked: 'The best thing a teachers can offer is the students become better than them.”

JO: You can have a really good professor and make you discover things. What I like about American school compared to France or China that this kind of connection between the best people in architecture and the school. 'Best' I say in certain way, you know. And because not everybody has the same opinion about architecture. I think the other thing is, that most of our students are very good when they get out of school and then they have to deal with professionals and they get hit.

It's very difficult for students to find work where it can be a development for them, the same time supporting architecture. The job they do is even bigger problem because 95% what Americans build is not architecture. Nothing historic, they are big but they are not architecture.

José Oubrerie: I think SCI-Arc is a great school. You have SCI-Arc, UIC, you have UCLA. We have a different way of where you stand and also what we try to do at Ohio State University. We show students a different way of working. For example in the past, Columbia University was fantastic, but it's been declining in the last years. The school was very active and also after that...

OA: Mark Wigley is very good.

JO: He doesn't like architecture.

OA: I saw him a few weeks ago in Shenzhen Biennale. He said something interesting. He said the architecture schools are mainly in crisis, which is good, and he said something that I liked: 'The best thing a teachers can offer is the students become better than them.”

JO: You can have a really good professor and make you discover things. What I like about American school compared to France or China that this kind of connection between the best people in architecture and the school. 'Best' I say in certain way, you know. And because not everybody has the same opinion about architecture. I think the other thing is, that most of our students are very good when they get out of school and then they have to deal with professionals and they get hit.

It's very difficult for students to find work where it can be a development for them, the same time supporting architecture. The job they do is even bigger problem because 95% what Americans build is not architecture. Nothing historic, they are big but they are not architecture.

OA: It is a market thing. How do you define architecture?

JO: What I do.

OA: What do you do?

JO: Not to make a building to just make a building, but start making a contribution to architecture. And you consider that you are not a star architect... If you want to make quick connections or meet big people to get jobs and play golf, you act commercially, and, what makes you get jobs is showing an example of what you did, you have to do something else.

OA: Do you feel like that part of the character you describe, you couldn't do it yourself and maybe that's why you did very few projects?

JO: It's a part of some architects, it depends, I mean, it's a question of networking. My late work is of only architecture... I am not included in the circles of the American society, I'm not a business man, I never was.

OA: Frank Gehry is a very good business man?

JO: He became a very good one. He is wanted by what he is doing.

Working for Corbusier was not that easy. When I started to work with him, I had not so much architectural education and it took me three years to really understand what we were doing.OA: I think he's a very good architect. Though, more of an analog guy. Kind of a happy sculpturalist. But I've never been in a Gehry space that wasn't good. I think popular media only knows him via his late work, the ones he shows to potential clients who want that kind of Gehry.

JO: He's trying out the formula. I like him, I have a met him several times.

Getting back to one building, remember Pierre Chareau - Maison de Verre Some has one project that was very good and that was enough.

OA: That's what I was going to bring up, the architects with few buildings. Ludwig Wittgenstein did one house for his sister but what a house that was, better than Adolf Loos. But he was a philosopher.

I guess that’s what you mean, you look at these architectures, you look at Miller house and you see, feel and you learn something about architecture. John Hejduk with few buildings is another one who is very good. Peter Eisenman too, the early houses.

JO: I think Peter is great too. He's the one who accomplished a big step in architecture.

OA: Remember, Philip Johnson with his five architects? Richard Meier, Michael Graves, Peter Eisenman, Charles Gwathmey, and John Hejduk.

JO: And apart from Hejduk, the only one who did something was Peter.

Peter with the Wexler Center because he subverted the modern discourse, invented and developed a new aspect of specialty, involving the issue of modern architecture and reinterpreting in his way. Richard Meier, on the other hand is much more successful commercially. He makes combinatorial Corbusian dilemmas.

OA: His first two three projects were interesting, then it became a...

JO: He became a post modernist modern...

JO: What I do.

OA: What do you do?

JO: Not to make a building to just make a building, but start making a contribution to architecture. And you consider that you are not a star architect... If you want to make quick connections or meet big people to get jobs and play golf, you act commercially, and, what makes you get jobs is showing an example of what you did, you have to do something else.

OA: Do you feel like that part of the character you describe, you couldn't do it yourself and maybe that's why you did very few projects?

JO: It's a part of some architects, it depends, I mean, it's a question of networking. My late work is of only architecture... I am not included in the circles of the American society, I'm not a business man, I never was.

OA: Frank Gehry is a very good business man?

JO: He became a very good one. He is wanted by what he is doing.

Working for Corbusier was not that easy. When I started to work with him, I had not so much architectural education and it took me three years to really understand what we were doing.OA: I think he's a very good architect. Though, more of an analog guy. Kind of a happy sculpturalist. But I've never been in a Gehry space that wasn't good. I think popular media only knows him via his late work, the ones he shows to potential clients who want that kind of Gehry.

JO: He's trying out the formula. I like him, I have a met him several times.

Getting back to one building, remember Pierre Chareau - Maison de Verre Some has one project that was very good and that was enough.

OA: That's what I was going to bring up, the architects with few buildings. Ludwig Wittgenstein did one house for his sister but what a house that was, better than Adolf Loos. But he was a philosopher.

I guess that’s what you mean, you look at these architectures, you look at Miller house and you see, feel and you learn something about architecture. John Hejduk with few buildings is another one who is very good. Peter Eisenman too, the early houses.

JO: I think Peter is great too. He's the one who accomplished a big step in architecture.

OA: Remember, Philip Johnson with his five architects? Richard Meier, Michael Graves, Peter Eisenman, Charles Gwathmey, and John Hejduk.

JO: And apart from Hejduk, the only one who did something was Peter.

Peter with the Wexler Center because he subverted the modern discourse, invented and developed a new aspect of specialty, involving the issue of modern architecture and reinterpreting in his way. Richard Meier, on the other hand is much more successful commercially. He makes combinatorial Corbusian dilemmas.

OA: His first two three projects were interesting, then it became a...

JO: He became a post modernist modern...

OA: You worked for Corbusier, what is to be learned from Corbu himself?

JO: That's difficult question to answer.

OA: Well you had a one to one relationship with him, so you know...

JO: Working for Corbusier was not that easy. When I started to work with him, I had not so much architectural education and it took me three years to really understand what we were doing. For me what I learned the most is how to make a decision, and when you address a problem or something in the project. So project becomes a construction of these decisions. He always would say, “let's make a reading of the project.” These were the self-evaluations between his goals and things. In the background he would think of all his theories. He was giving us directions to solutions and if you were not understanding and you made something else, he would tell you “it's very interesting, but keep it for yourself.”

OA: (laughter) Do you feel like whatever you learned from Corbusier you took further, and maybe you did with Miller house? How do you feel about this question?

JO: For me, I have two projects that have been important to me for my development. The building I did in Syria, the French Cultural Center and the Miller House. Cultural Center was a very close interrogation of Villa la Roche. And the other was the Miller House, which we worked with the language in which we were working. When I start to build and after I did these two projects, I kept my education and what I understood from Corbusier alive. What I experienced with these two projects was very important to me. Also the Firminy Church was finished in 2003 and I said “Oh my god, I was seventeen when I started the church.” So, at this moment I was happy my church was finished so I could do other things.

OA: How did you get the job from Corbusier?

JO: I told him that I can do the work.

It's very difficult for students to find work where it can be a development for them, the same time supporting architecture.OA: Corbusier designed a master plan for Izmir, Turkey and later he went to Chandigarh.

JO: He was ready to experiment things.

OA: Years later I look at the plans of Izmir and they adopted few things, maybe I am imagining. But there is nothing like he designed. Plus, I think they short-changed him for wanting to erase the whole historical core of the city...

The other day my friend asked me, “What do I think about the Miller house?” I said, to me, as it was taught in architecture school, that it was a Corbusier thing that everything was kind of orthogonally structured in four sections, creating various opportunities between those sections and many times inserting an organic form in it instead of an orthogonal confines of the squares. It is very clear in Olivetti plans. You don't have the kidney shapes but...

JO: Yes it was the same thing. For me the most important would define the house was to design it like a small city. The house is like a city and the city like a house. The inside was affected by different cities and for me that was very important, which was generating the house. We look at the family as the organization. That translated to kinds of plans which escaped from the typical plans of living room, dining room, blah blah… that’s a terrible thing...

You have to redefine the program, the program of the house, to me that had to be redefined. That was the first stage. If I was doing another house I would even redefine it in a more interesting way.

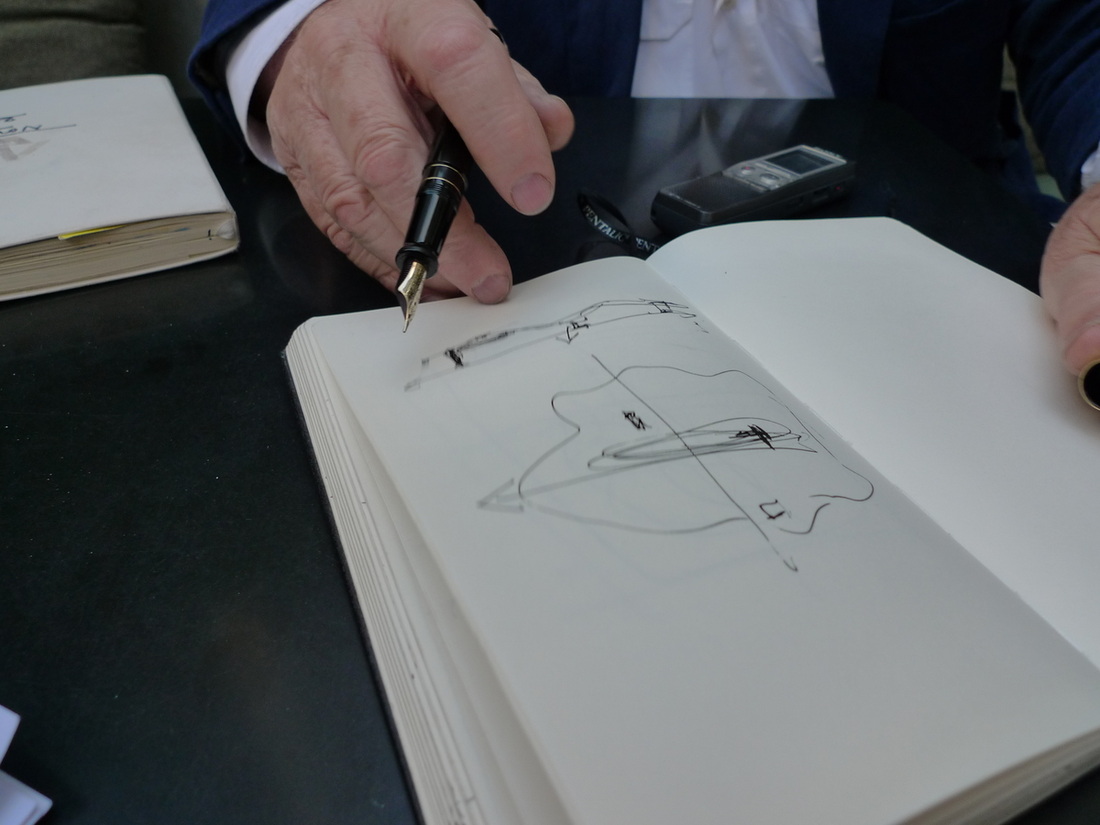

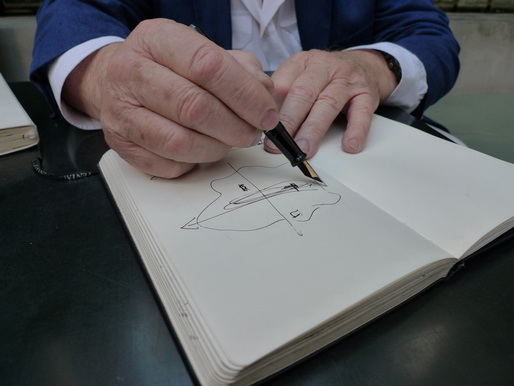

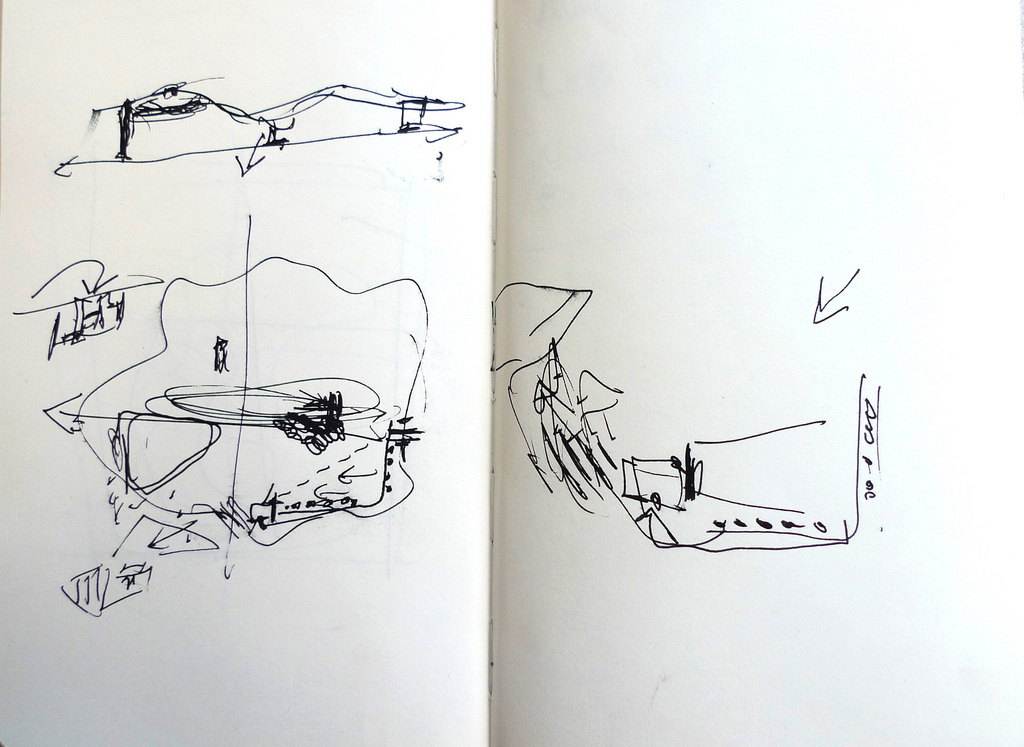

Getting back to your question about the site plan you asked at the book event, the site was something like that. Here we put the middle house. After I put the house here it was to look this way (starts drawing in Orhan’s notebook). This is the idea that the other house was somewhere. Like a subdivision. The main thing was that, here you have the wall of trees where you were walking with water. The project I did, I put a lot of trees here to hide this house (keeps drawing, explaining the site plan.)

JO: That's difficult question to answer.

OA: Well you had a one to one relationship with him, so you know...

JO: Working for Corbusier was not that easy. When I started to work with him, I had not so much architectural education and it took me three years to really understand what we were doing. For me what I learned the most is how to make a decision, and when you address a problem or something in the project. So project becomes a construction of these decisions. He always would say, “let's make a reading of the project.” These were the self-evaluations between his goals and things. In the background he would think of all his theories. He was giving us directions to solutions and if you were not understanding and you made something else, he would tell you “it's very interesting, but keep it for yourself.”

OA: (laughter) Do you feel like whatever you learned from Corbusier you took further, and maybe you did with Miller house? How do you feel about this question?

JO: For me, I have two projects that have been important to me for my development. The building I did in Syria, the French Cultural Center and the Miller House. Cultural Center was a very close interrogation of Villa la Roche. And the other was the Miller House, which we worked with the language in which we were working. When I start to build and after I did these two projects, I kept my education and what I understood from Corbusier alive. What I experienced with these two projects was very important to me. Also the Firminy Church was finished in 2003 and I said “Oh my god, I was seventeen when I started the church.” So, at this moment I was happy my church was finished so I could do other things.

OA: How did you get the job from Corbusier?

JO: I told him that I can do the work.

It's very difficult for students to find work where it can be a development for them, the same time supporting architecture.OA: Corbusier designed a master plan for Izmir, Turkey and later he went to Chandigarh.

JO: He was ready to experiment things.

OA: Years later I look at the plans of Izmir and they adopted few things, maybe I am imagining. But there is nothing like he designed. Plus, I think they short-changed him for wanting to erase the whole historical core of the city...

The other day my friend asked me, “What do I think about the Miller house?” I said, to me, as it was taught in architecture school, that it was a Corbusier thing that everything was kind of orthogonally structured in four sections, creating various opportunities between those sections and many times inserting an organic form in it instead of an orthogonal confines of the squares. It is very clear in Olivetti plans. You don't have the kidney shapes but...

JO: Yes it was the same thing. For me the most important would define the house was to design it like a small city. The house is like a city and the city like a house. The inside was affected by different cities and for me that was very important, which was generating the house. We look at the family as the organization. That translated to kinds of plans which escaped from the typical plans of living room, dining room, blah blah… that’s a terrible thing...

You have to redefine the program, the program of the house, to me that had to be redefined. That was the first stage. If I was doing another house I would even redefine it in a more interesting way.

Getting back to your question about the site plan you asked at the book event, the site was something like that. Here we put the middle house. After I put the house here it was to look this way (starts drawing in Orhan’s notebook). This is the idea that the other house was somewhere. Like a subdivision. The main thing was that, here you have the wall of trees where you were walking with water. The project I did, I put a lot of trees here to hide this house (keeps drawing, explaining the site plan.)

OA: I saw something here on the site… Another house, it's awful. How do you feel about this?

JO: What can you do?

OA: Usually homes have front and back, but Miller House doesn't have a front or back. Evan Chakroff wrote very well about the elevations of this house.

JO: Yes indeed. It's a recollection of the front facade. You enter everywhere.

OA: It’s an occurring problem with houses. It needs to be all four sides. What do we learn from these houses? All the students are extremely fascinated about the details.

JO: Architecture should be done this way. I did also bad buildings. It was a building in Paris. I had not enough experience with working with France and their regulations. When you working with something like the city of Paris, you don't know. I like Boston very much. It’s starting to be connected. It starts to be manipulated in a different way. (He explains the site plan.)

OA: Do you have any prospect of getting any new projects? Does your telephone ring?

95% what Americans build is not architecture. Nothing historic, they are big but they are not architecture.JO: I have no idea. My telephone doesn’t ring... Even when I finished the church I was thinking maybe someone will call me… nothing... I don't know. I do competitions. I start to make competitions because they are always interesting.

OA: What scale?

JO: Anything... Any scale. I don’t believe in big city plans, working with big developers. I don't know.

OA: A single building is always a start. That's why the houses are important. You can get corrupted by the big developers.

JO: Yes. Not only monetarily but design-wise as well.

OA: Not to change the subject but Oscar Niemeyer designed a house in LA.

JO: I didn't know.

OA: A Los Angeles house, it's beautiful, it's in Santa Monica.

JO: I want to see the Schindler house.

OA: I can take you there if you like.

JO: Where do you live?

OA: Doesn’t matter where I live, I am looking for a place to drive. It's an LA thing...

JO: (Laughs)

OA: Thank you Mr. Oubrerie. Have you seen Wilshire Boulevard?

Editor's note:

This is a re-print of the actual article published in Archinect. See the link below for the original article with reader commentary here.

JO: What can you do?

OA: Usually homes have front and back, but Miller House doesn't have a front or back. Evan Chakroff wrote very well about the elevations of this house.

JO: Yes indeed. It's a recollection of the front facade. You enter everywhere.

OA: It’s an occurring problem with houses. It needs to be all four sides. What do we learn from these houses? All the students are extremely fascinated about the details.

JO: Architecture should be done this way. I did also bad buildings. It was a building in Paris. I had not enough experience with working with France and their regulations. When you working with something like the city of Paris, you don't know. I like Boston very much. It’s starting to be connected. It starts to be manipulated in a different way. (He explains the site plan.)

OA: Do you have any prospect of getting any new projects? Does your telephone ring?

95% what Americans build is not architecture. Nothing historic, they are big but they are not architecture.JO: I have no idea. My telephone doesn’t ring... Even when I finished the church I was thinking maybe someone will call me… nothing... I don't know. I do competitions. I start to make competitions because they are always interesting.

OA: What scale?

JO: Anything... Any scale. I don’t believe in big city plans, working with big developers. I don't know.

OA: A single building is always a start. That's why the houses are important. You can get corrupted by the big developers.

JO: Yes. Not only monetarily but design-wise as well.

OA: Not to change the subject but Oscar Niemeyer designed a house in LA.

JO: I didn't know.

OA: A Los Angeles house, it's beautiful, it's in Santa Monica.

JO: I want to see the Schindler house.

OA: I can take you there if you like.

JO: Where do you live?

OA: Doesn’t matter where I live, I am looking for a place to drive. It's an LA thing...

JO: (Laughs)

OA: Thank you Mr. Oubrerie. Have you seen Wilshire Boulevard?

Editor's note:

This is a re-print of the actual article published in Archinect. See the link below for the original article with reader commentary here.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed